You don’t have to be in a funk just because it’s Monday. Instead, get funky!

You don’t have to be in a funk just because it’s Monday. Instead, get funky!

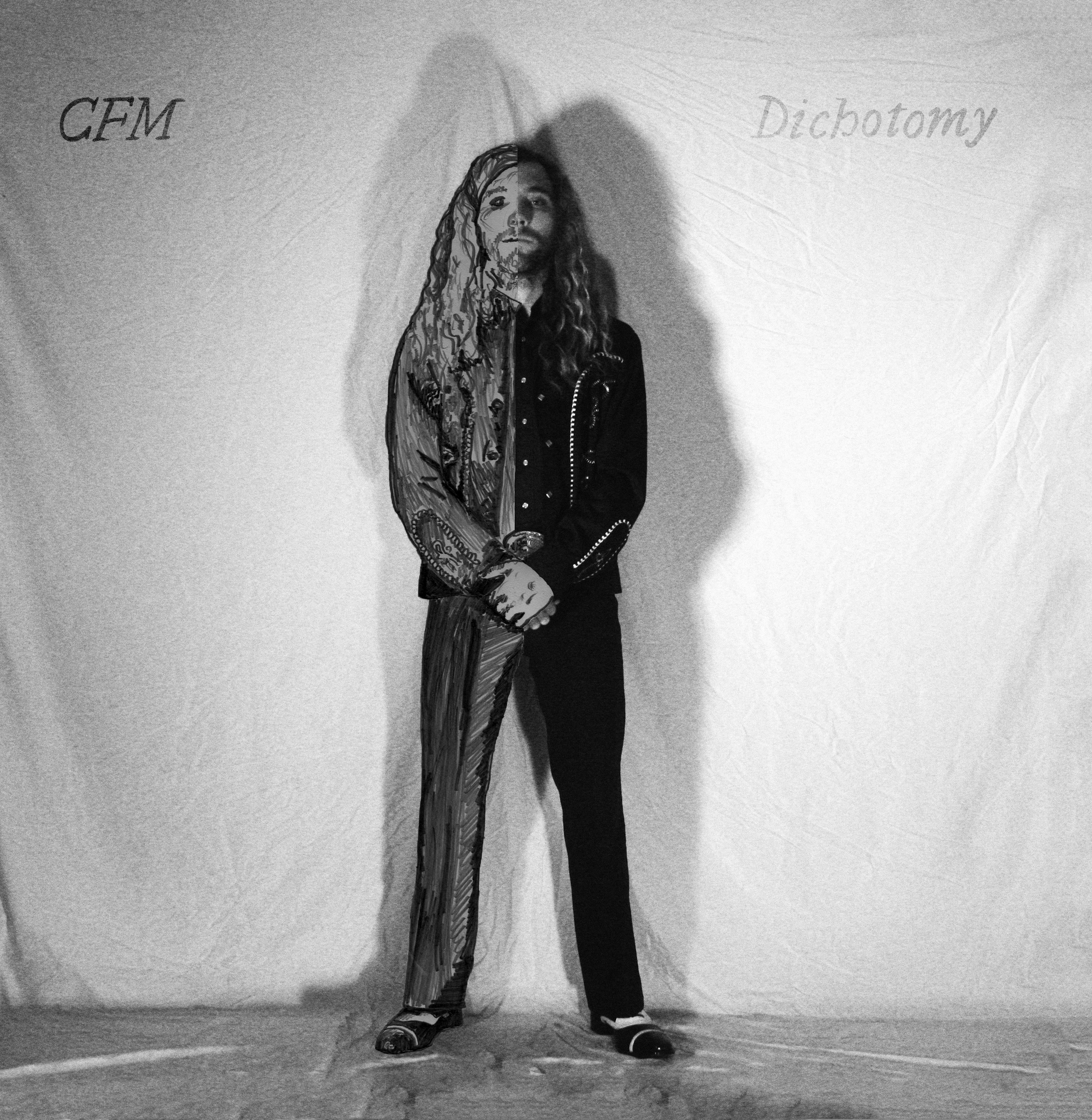

TrunkSpace brings you another edition of Musical Mondaze. This time out we’re sitting down with Charles Moothart, a shredding multi-instrumentalist who has performed alongside Ty Segall for years, including in the hard rock band Fuzz, which formed in 2011. Most recently Moothart has returned his focus to his own side project, CFM, to release his second studio album, “Dichotomy Desaturated.”

We recently sat down with Moothart to discuss juggling his various projects, feeling vulnerable with his solo work, and how he tends to come up with new riffs or chord progressions.

TrunkSpace: You create and perform in a number of different bands/projects. Do you view them all as separate islands or do they connect for you creatively in some way?

Moothart: Generally I try to view everything I do as separate. There are certainly moments where you’re working on a song or an idea is kind of floating around and I might not necessarily know where it will end up or where it will land or what the end idea will be. It’s not like I try to be super militant about keeping things separately, but when it comes down to it, yeah… I try to keep everything separated and let everything kind of exist in its own realm, at least mentally.

TrunkSpace: What about on stage? Do you ever blend those different realms together?

Moothart: Yeah, that’s definitely one side of it. Everybody I’m involved with, we try to keep it all separate. There are definitely times where people will ask, if I’m playing with Ty or something, people will be like, “Are you going to play a Fuzz song?” You definitely try to keep things separated that way.

TrunkSpace: What were your goals with “Dichotomy Desaturated” and as you listen back now, do you feel like you achieved those goals?

Moothart: Yeah. Definitely. The last record kind of came about somewhat indirectly, so once I kind of took that stuff out and started playing live, I wanted to go in to making a record that would kind of have the lessons I had learned from playing songs live and include those in the songwriting process and just go into it with a more direct idea of actually trying to write a fully cohesive record. So yeah, in that way, definitely. I’m proud of the record. There’s a lot of things on it that are scary to me. The whole thing generally feels very vulnerable, so in another way, I can listen to it and hear things that I would do differently, but not necessarily in a bad way. In that way I’m also happy with it because I feel like it points out things to me… some things that I could work on. It kind of allows me to go out of body and kind of become critical of certain ideas, which to me is also a bonus. I don’t look at that as a negative.

TrunkSpace: Does that mean that you then take those things that you would have wanted to do differently and apply those changes to the way you’re playing the songs live?

Moothart: Yeah. A lot of these songs from this record… we haven’t really gotten to play live. We’ve started playing a couple of them and right now we’re working on learning the rest of them. But  yeah, I definitely hope to tweak some things live just to keep it… even just beyond what I would want to change, just to make it more interesting because there are certain things that I think translate on the record that maybe wouldn’t translate as well live. So, I definitely want to be able to switch it up, but it’s also just more of a future reference kind of thing with certain ideas or certain kind of song characteristics just for writing in the future. It’s just kind of more like a mental note. Like, “You were trying to do this and this is kind of the way that it would maybe translate better to a listener.”

yeah, I definitely hope to tweak some things live just to keep it… even just beyond what I would want to change, just to make it more interesting because there are certain things that I think translate on the record that maybe wouldn’t translate as well live. So, I definitely want to be able to switch it up, but it’s also just more of a future reference kind of thing with certain ideas or certain kind of song characteristics just for writing in the future. It’s just kind of more like a mental note. Like, “You were trying to do this and this is kind of the way that it would maybe translate better to a listener.”

TrunkSpace: You mentioned you feel vulnerable with this record. Was there anything musically that you tried differently in the songwriting or recording that sort of emphasizes that feeling?

Moothart: Yeah. For sure. The biggest one is… really, most of it just kind of comes down to songwriting because that’s kind of something that’s always been elusive to me. I like writing riffs and I like writing chord progressions, but vocal melodies are something that I’m still trying to wrap my head around because I’m still trying to figure out… singing. (Laughter) So yeah, a lot it is just kind of trying to find more of a groove with songs or let songs kind of sit in their own space because my brain tends to want complicate things or make things more intricate. I guess that’s kind of just where I immediately go. I think about how I can switch everything up to keep it, just like, constantly changing. To me that’s what makes something interesting, but in reality sometimes it’s more interesting to just be able to have someone who is listening to just be kind of captivated by just the idea of what’s happening or the groove that the song sits in. More stuff like that. On the record there’s more acoustic moments or mellower moments where the idea would be, hopefully, that people can actually just listen to it and be kind of sucked in. And then that allows for the louder moments of the record to actually kick instead of it being, like, all right in the front. So that’s a big thing for me.

TrunkSpace: Is one of the benefits of playing live being able to extend those groove moments you were just referencing? If you can tell that an audience is enjoying the ride, you can just kind of prolong the ride for as long as you like, right?

Moothart: For sure. Both sides have that effect in a different way. The interesting thing too with what you’re saying with live is sometimes there’s a song that you’re not sure what it’s all about or maybe you don’t think it’s a really strong idea, and then sometimes those are the songs that people react to the most and you’re like, “Whoa… what about that is what people like?” That’s where I mentioned going out of body… it’s always hard to be self-critical and understand what someone else is going to hear it as because when you have your own idea, you kind have already decided what the song sounds like but you don’t know what it sounds like to someone who isn’t in your head. I think that’s the overall long term goal. I think that’s what, I don’t know, for lack of a better word… what great musicians or great performers or great songwriters… whatever that means in whatever genre, they’re able to do is kind of like tweak things as they go and be able to read a certain situation. You should be able to be open to what the people who are listening want. Not that that should always be your first priority, but if people are there to enjoy your music then you should hopefully be able to go with that and read what that means.

TrunkSpace: How does a guitarist transcend from playing guitar really well and playing whatever they want to sort of having that signature sound where as soon as you hear the riff you know it’s that particular guitarist? What is that thing that clicks and then all of a sudden somebody just has their own sound?

Moothart: Man, I have no idea. I really don’t know. That’s something I’m trying to wrap my head around. To me, a huge one for that is the Velvet Underground. As soon as the Velvet Underground or any Lou Reed song starts playing, you’re like, “Oh… that’s Lou Reed.” And to me, that goes to what I was talking about… find the groove. That dude knows how to sit in the fucking groove forever. (Laughter) And it’s like endlessly captivating. I have no idea. That’s like the fucking holy grail… a coveted secret. But, I feel like a lot of it comes down to people kind of just trying to remove themselves from any kind of outside expectation or just kind of letting things come to them exactly as they want and not being scared of something either sounding similar to what they have done before or similar to something else. Kind of just having that faith that their ideas is their idea and that’s what they want to do, so fuck it and go for it. To me, that’s kind of the main idea. It’s the same with The Stooges. All of The Stooges music is on a base level, basic, but no one else could do it. To me that’s it. It’s not really caring about anything, I guess.

TrunkSpace: Would a part of that also be not relying too heavily on influences because, once you put too much of them into yourself, then all of those elements become a part of your work as opposed to your work being wholly original?

Moothart: Exactly. And then it’s just going to sound regurgitated. Yeah. And it’s funny you say that because there’s been a couple of times when… it’s interesting when people ask, and I totally understand the question, but, “What are your influences?” I appreciate and understand that question, but it’s also a hard question to answer because the idea at the end of the day is to not necessarily have your influences be… you should wear your influences on your sleeve and never hide from them, but you also don’t want to just sound like them. It shouldn’t be immediately accessible, unless that’s what you’re going for, which is cool too.

TrunkSpace: So then maybe the influence question would be better served as, “What artists made you love music?”

Moothart: Yeah. Yeah. For sure. Totally. (Laughter)

TrunkSpace: That’s a good segue into our next question. We read that you picked up your first guitar at 12. Was music a big part of your life even before that?

Moothart: It was, I think, more than I realized. My parents were both really into music. Neither of them are musicians or anything, but my mom definitely, around the house and in the car, she was always playing music. And my sister and my mom would always be singing along to songs and they were really good with lyrics or picking up people’s lyrics, which is something I’ve never been good at. In retrospect, yeah, my mom was definitely always playing music. When I started playing instruments, they were stoked. They wanted me to be exploring that, so in that way, for sure. I feel lucky to have had that influence, but it wasn’t something that at the time… like, I wouldn’t have looked back and thought that music was a huge part of my life as a kid, but then I talk about it with other people and some people didn’t have that experience. I definitely feel lucky for that.

Moothart: It was, I think, more than I realized. My parents were both really into music. Neither of them are musicians or anything, but my mom definitely, around the house and in the car, she was always playing music. And my sister and my mom would always be singing along to songs and they were really good with lyrics or picking up people’s lyrics, which is something I’ve never been good at. In retrospect, yeah, my mom was definitely always playing music. When I started playing instruments, they were stoked. They wanted me to be exploring that, so in that way, for sure. I feel lucky to have had that influence, but it wasn’t something that at the time… like, I wouldn’t have looked back and thought that music was a huge part of my life as a kid, but then I talk about it with other people and some people didn’t have that experience. I definitely feel lucky for that.

TrunkSpace: When it comes to writing riffs or chord progressions… do you need to have a guitar in your hand to come up with a concept for a song, or can it start out in your head or as a hum?

Moothart: Most of the time it’s through playing an instrument. I’m pretty much constantly playing guitar throughout the day. I’ll do it even if it’s for like five minutes or whatever. I’m kind of always picking it up and putting it down, so a lot of things will just kind of come from there. There are rare moments where I’ll be walking around or driving around and a riff will kind of pop into my head. I’m trying to get better at dissecting that because usually I just forget it. That does happen sometimes, but it’s always interesting when that happens for me because when I try to translate it to guitar, I’m not connecting. It’s almost like two separate parts of my brain, but I’m trying to bring them together. “I hear this, but how do I play it?” And then I’m playing it and it’s like… sometimes I can’t figure out what the fuck was in my head and then I forget it most of the time. (Laughter)

TrunkSpace: That is something that is really impressive about musicians, especially prolific ones… the ability to remember all of the songs that they have written and not confuse them with other songs that they have written. Are there moments where you’re writing and you come up with an amazing idea and all of a sudden it’s gone?

Moothart: Oh yeah! All the time. It’s really frustrating. (Laughter)

TrunkSpace: Will you record ideas even in their early stages?

Moothart: Yeah. That’s probably my favorite part of my iPhone. Not to be hawking iPhones. But yeah, the voice memo on the iPhone… that’s my saving grace a lot of times. If I have an idea, I’ll record it and then kind of just keep playing. There’s a time where I forget a riff within literally like, two minutes. I’ll be playing it and then I’ll play a different chord progression and then I’ll try and go back to that riff and it’s gone. It’s all about the smaller parts… the rhythm of something… that is always hard to return to. You can remember what notes you played, but it’s the rhythm.