Michael J. Fox, in a DeLorean, while we both sipped Hi-C Ecto Cooler in the year 1955. That’s the only interview circumstance that our inner child would have found more exciting than getting the chance to have a dinosaur-sized conversation with paleontologist Steve Brusatte. Seriously, as lifelong terrible lizard lovers, we’re downright giddysaurus!

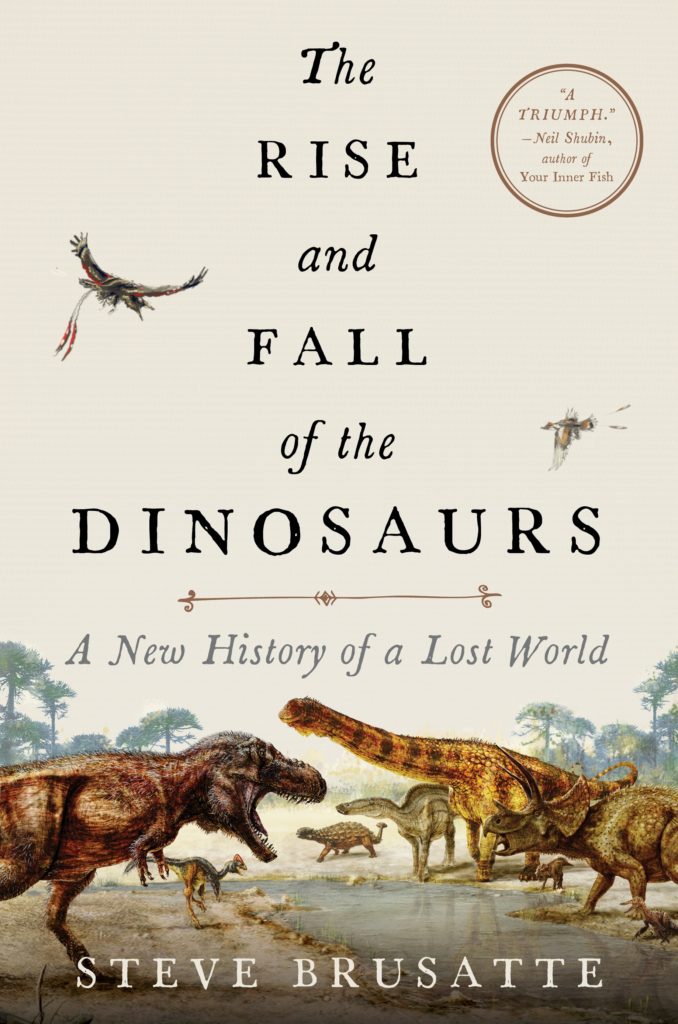

The accomplished paleontologist-turned-author recently released the scientifically-focused “The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World,” a book written for adults who never stopped staring wide-eyed at the distant past. We recently sat down with Brusatte to discuss dino enchantment, how our view of the long-extinct creatures has changed over the years, and why the Therizinosaurus needs a better publicist.

TrunkSpace: Like so many kids before and after you, were you mesmerized by dinosaurs at a young age and is that where your career as a paleontologist first began? Can you pinpoint an exact moment where a love for dinosaurs and discovery cemented themselves in your young mind?

Brusatte: Strangely enough, I wasn’t one of THOSE kids – the five year olds who know the name of every dinosaur, down to the proper spelling and pronunciation. I meet kids like that all of the time now when I go into schools to talk about dinosaurs. But when I was in elementary school, I wasn’t interested in science at all. It was my least favorite class. My brother Chris, though, he was obsessed with dinosaurs. He turned his bedroom into a dinosaur museum and library. And slowly, through osmosis, his enthusiasm infected me and I became enthralled with dinosaurs when I was in high school, and haven’t stopped since.

TrunkSpace: As someone who has been on the other side of the wonderment starting in high school, why do you think dinosaurs are sort of timeless in their ability to captivate people of all ages? And in addition to that, has your own wonderment waned at all over the years or has it only increased?

Brusatte: I’ve gotten more cynical about certain things as I’ve gotten older. Politics especially. And professional sports! But not dinosaurs. Whenever I walk into a museum, I still feel that same enchantment that I did when I was a teenager going to the Field Museum in Chicago to see their dinosaurs. I can’t quite put words to it, as I think it’s more magic than logic. But there is just something indescribable about dinosaurs. I think they are more fantastic than dragons or sea monsters or unicorns or anything humans have ever invented in myths and legends, but they were REAL!

TrunkSpace: The way people view dinosaurs has changed a lot in recent years. When we were kids, we were taught that they were distant relatives of reptiles, but now, it’s widely understood that they’re more closely related to birds. Do you think there are more discoveries in this category to be had – the kind that change the way we view dinosaurs as a whole?

were distant relatives of reptiles, but now, it’s widely understood that they’re more closely related to birds. Do you think there are more discoveries in this category to be had – the kind that change the way we view dinosaurs as a whole?

Brusatte: Totally. I still remember the dinosaur books in my school library, and the way dinosaurs were portrayed in our textbooks. They were these dim-witted, slow-moving, drab-colored idiots, just kind of sitting around waiting to go extinct. And this wasn’t too long ago – this was the late 1980s and the 1990s! But now we know this is completely incorrect. Dinosaurs were nature’s ultimate success stories. They were an empire that ruled the world for over 150 million years, and many of them were fast, smart, dynamic, active, and energetic. And yes, they were much more like birds than reptiles. A lot of them even had feathers. The discovery of the first feathered dinosaurs in the late 1990s was a gamechanger. But who knows what the next ground-shifting discovery will be? That’s the exciting – and addictive – thing about a science like paleontology. You can never predict what somebody’s going to find next.

TrunkSpace: We would imagine that feathers are not easy to preserve, especially over the course of 66 million years or so. Has technology made those discoveries possible, or is a big part of it being in the right place at the right time and stumbling upon the preserved evidence?

Brusatte: Feathers are so hard to preserve. It was actually back in the 1860s, during the time of Darwin, that the great British scientist Thomas Henry Huxley first proposed that birds evolved from dinosaurs. He noticed many similarities in their bones. But the idea was controversial for well over a century, until the feathered dinosaurs were found in northeastern China in the late 1990s. That ended the debate. The reason it took so long to find them is that soft things like feathers, skin, muscles, and internal organs are really hard to preserve as fossils. They decay really quickly, or get eaten by predators. Most fossils are hard stuff like bones, teeth, and shells. These dinosaurs in China had the great misfortune to live in a lush jungle that was periodically buried by volcanoes, almost Pompeii style, and so they were entombed in rock really quickly, going about their everyday business, and the feathers didn’t have time to decay. It wasn’t new technology that found these amazing fossils, but farmers in northeastern China, working their land. Right place at the right time I suppose – but these farmers are amazing. They keep finding feathered dinosaurs. They know all of the best spots. There are thousands of feathered dinosaur skeletons that have now been found!

TrunkSpace: Many of the dinosaurs that the general public have become familiar with never actually existed during the same time as each other. Is one of the biggest misconceptions about dinosaurs the idea that ALL species walked the Earth at the same time?

Brusatte: Yes indeed, it’s what we call the Jurassic Park Fallacy! The films show lots of dinosaurs from different places and time periods living together. Of course that’s fine because they’re cloned dinosaurs living in a theme park, and the film is entertainment and not a science documentary, so I won’t complain! But it does perhaps give this impression that all dinosaurs lived everywhere at once. But the world of dinosaurs was like our modern world: different species lived in different places, and the species changed over time. New ones evolved, old ones went extinct. How’s this for a fact to blow your mind? T. rex (which lived 66 million years ago) is closer in time to us than it was to Stegosaurus and Brontosaurus (which lived about 150 million years ago). Digest that one!

TrunkSpace: What is a species of dinosaur that you feel deserves more publicity? For us, it’s the Dimetrodon, though if we remember correctly, it’s not actually a dinosaur, but man, that fin is pretty awesome! What about you – what dino would you love for more people to learn about?

Brusatte: First off, you’re totally right about Dimetrodon: it’s not a dinosaur (it’s a primitive relative of mammals, believe it or not), but it is awesome and deserves a better publicist. As for a dinosaur that’s still inexplicably yet to make its big break, I would go with Therizinosaurus. This is a member of the meat-eating dinosaur group that switched to a vegetarian diet. It was almost 30 feet long, with eight-foot-long arms capped with Edward Scissorhands-style scythe claws. It had big bulky legs and enormous feet, but probably only a tiny little head. This was one weird dinosaur. It needs a better agent.

TrunkSpace: You recently released the book “The Rise And Fall Of The Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World.” What were your goals when you set out to put the book together and did you achieve them when all was said and done?

Brusatte: There are so many books about dinosaurs for kids. If you go to a bookstore, or to a library, you might see hundreds of them. But there aren’t so many dinosaur books for adults. And I find that really weird, and a big shame, because dinosaurs were awesome, and they have a lot to teach us. These were the animals that ruled the world before humans, and their evolutionary story reads like fiction, but it actually happened! That’s the story I tell in the book: how the dinosaurs started humble and gradually rose up to dominance, how they then spread around the world and grew to huge sizes, how some got smaller and developed feathers and became birds, and how the rest of them suddenly died out when the environment quickly deteriorated. Throughout, I try to spice it up with my own stories of digging up dinosaurs around the world, and stories of my many amazing colleagues – particularly the young women and men who have grown up in this post-Jurassic Park generation and are fueling a golden age in dinosaur research.

TrunkSpace: What was the process of writing the book like for you? Is writing a labor of love or does it feel more like labor?

Brusatte: Completely a labor of love. My day job is a standard academic researcher job at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. It’s a wonderful job: I teach classes, I run a lab, I advise graduate students, I write grants and serve on committees, I do fieldwork and describe dinosaurs, and I do a lot of outreach. I think that engaging with the public is really important, and also really fun. People need to know about the science we’re doing. If we hide it away behind university doors, and within the pages of specialist research journals, then who does that benefit? Who does that inspire? I had to find nuggets of time when I wasn’t teaching or doing fieldwork to write the book, but I enjoyed it so much and hope I get the opportunity to write another one someday!

TrunkSpace: In the book you reference the present day being the “golden age of paleontology” with about 50 new species being discovered every year. At the same time, it feels like we’re living in an age where science is being pushed aside and marginalized. Is there concern within the scientific community that the golden age will end due to a lack of funding and interest from future generations?

Brusatte: It is the golden age, no doubt. Somebody, somewhere, is finding a new species of dinosaur once a week on average! And that has been happening for the past decade. It’s all because paleontology has become a global science, and it’s countries like China, Argentina, Brazil, and Mongolia that are leading the way these days. Young scientists in these countries, and all around the world, are the engine behind this boom. I have no doubt that there are tons of dinosaurs still out there to be found. But I do worry that in our modern politically-inflamed culture wars, that science is seen as a partisan thing, the purview of elites, and a threat to the way of life and beliefs of many people. That’s really nonsensical. Most scientists like me are overgrown children who are so giddy about the natural world that we want to explore it and understand it.

Brusatte: It is the golden age, no doubt. Somebody, somewhere, is finding a new species of dinosaur once a week on average! And that has been happening for the past decade. It’s all because paleontology has become a global science, and it’s countries like China, Argentina, Brazil, and Mongolia that are leading the way these days. Young scientists in these countries, and all around the world, are the engine behind this boom. I have no doubt that there are tons of dinosaurs still out there to be found. But I do worry that in our modern politically-inflamed culture wars, that science is seen as a partisan thing, the purview of elites, and a threat to the way of life and beliefs of many people. That’s really nonsensical. Most scientists like me are overgrown children who are so giddy about the natural world that we want to explore it and understand it.

TrunkSpace: You’ve been responsible for naming 15 new species of dinosaurs. When all is said and done and you hang up your Indiana Jones hat (we assume that every paleontologist wears a fedora!), what do you hope your legacy is? What do you want to be known for?

Brusatte: I wear more of a floppy fishing hat while in the field. It’s easy to pack and covers my whole face and neck during those long, hot days in the sun. My wife hates it, says it looks ridiculous and dorky. But it works! No sunburns. Some paleontologists do wear fedoras though. I’ve even known a couple of them to carry bullwhips in the field for some reason, I guess just to look the part of Indiana Jones. Bullwhips do not help us find or dig up dinosaurs, I can assure you! Anyway, when it comes to my legacy, I haven’t thought about that! I think (hope) I’m far too young to begin thinking about how I’ll be remembered. I’m just having a lot of fun, trying to discover new things about the world, trying my best to work collaboratively and train a new generation of students, and trying to communicate my enthusiasm to the public.

TrunkSpace: Finally, Steve, is there a way to articulate for our readers the feeling you get when you make a new discovery? What emotions rush to the surface when you uncover something that hasn’t been seen for millions and millions of years?

Brusatte: I’m normally a quite ebullient person, and my book is full of all sorts of flowery adjectives and other thesaurus words. But when it comes to describing the moment of discovery, I find it really hard to articulate. There is something amazing about being the first person to find a fossil, the first person to ever see it, the first person to glimpse something that lived millions (or tens or hundreds of millions) of years ago. But I don’t think that does it justice. It’s like trying to describe love. How can you really do it?

“The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World” is available now from William Morrow.