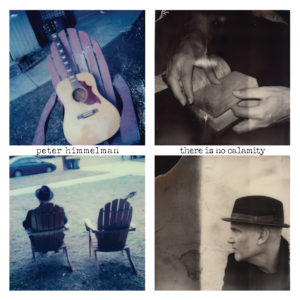

People have been enjoying the music of Peter Himmelman for decades, some without ever having realized it. As a successful composer for Hollywood film and television projects like “Bones” and “Judging Amy,” the Minnesota-native’s work has trickled into our subconscious and has been hummed from our lips, but it is his moving and thought-provoking solo work that stays with you on an emotional level. His latest album “There Is No Calamity” would be a page turner if it were a book, each track representing a chapter in a story that becomes more clear the deeper you dive into the context.

People have been enjoying the music of Peter Himmelman for decades, some without ever having realized it. As a successful composer for Hollywood film and television projects like “Bones” and “Judging Amy,” the Minnesota-native’s work has trickled into our subconscious and has been hummed from our lips, but it is his moving and thought-provoking solo work that stays with you on an emotional level. His latest album “There Is No Calamity” would be a page turner if it were a book, each track representing a chapter in a story that becomes more clear the deeper you dive into the context.

We recently sat down with Himmelman to discuss how his albums are journal-like records of his life, how he views his legacy, and why some people don’t make their dreams a reality.

TrunkSpace: Your discography features dozens of albums, both solo and as a member of bands. As you look back over those albums, how do you view them in terms of your life? Do they define specific periods in time for you?

Himmelman: It’s a good question. It has a little bit of meat on it for me, which I like to dive into. I started doing a little thinking about my catalog lately. I think because for reasons, good or ill, I never made an album with the intention of like, “I’m going to just get a single here” or never was I prodded by any record label to do so. It seems as though I was always given a lot of license just to write things that I was interested in, reflections of what I was thinking at the time or snippets of conversation.

Into that extent, you’re absolutely right. They leave a very journal-like record of exactly where I was at the time. My oldest son, who’s 27 now, he says for him, he remembers all those records when he was a kid and what they meant to him then and now. It’s almost the same way I remember when he was going to school and he was playing with trucks or something when he was four. They all have an impact.

I think they’re drawn from very personal observations and what meanings that were gleaned from those observations as opposed to a calculated look at songwriting. I’m not deriding that. After my first solo record, which was called “This Father’s Day” and it was based around a song that I had written for my dad when he was dying of lymphoma, that was really the change for me from tactical writing, which I still can do and sometimes do some of. I never feel, especially now, compelled to put those on my records. Especially now since making records has become just more of a personal passion than a means to deriving an income.

TrunkSpace: From a listener standpoint, putting on a song can instantly trigger of a memory. Same thing with smells. You smell a certain dish, you’re reminded of your childhood. To be involved in the creative aspect of those songs, there must be a different level of that memory trigger?

in the creative aspect of those songs, there must be a different level of that memory trigger?

Himmelman: Yeah. Your question now sparked something in me. Some of the songs that I am most connected to, and you have to understand that I write when I go through these periods of writing a lot. The most connected songs, at least for me, they were always born out of some kind of mystery. I was in a mood, and this just sounds like an old thing that people say, but they just pour out. In that sense, what I’m trying to get at is that they are often as mysterious to me as to a listener. Those are the kind of songs that I like in general. They’re fairly oblique. People can bring their own story to the song and it gives me a hint as to what was going on subconsciously in my life during those periods… periods of struggle, periods of joy, periods of youthful lust, or whatever. It’s all in there. Look, whereas I never had a giant hit or anything, I’m always scanning the horizon for, “So what is fulfilling about this?”

There’s something deeply fulfilling about looking back and seeing what I consider for myself a rich treasure trove or legacies.

TrunkSpace: You mentioned your son. Being able to have that recorded history, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be music… it could be anything… it’s a great thing to pass down to your kids because so many people don’t ever really get to KNOW their parents.

Himmelman: I was going to actually finish that sentence and I thought better of it. Maybe that’s too… but you took it.

Yeah, the legacy piece is something I never thought about. Maybe I was just too young to think about it. The more we know about our parents and their history, it’s always fascinating of course because we derive from them. So much of what they went through is a part of us, whether experimentally or genetically… however these things pass down.

Yeah, I think of the legacy not so much for the public, but for people close to me. Furthermore, when I write songs, the audience for them, at least in my mind who am I writing for, it’s usually just one person or a couple people. It’s not a mass. It’s a note to my wife or a couple musician friends of mine that I’d like them to hear or some person I think I’ll never get to talk to. It’s always a very small group. My kids are always in there, too. There’s certain things, probably certain things I won’t say in a song.

TrunkSpace: Knowing that those people you’re speaking to in the songs are listening?

Himmelman: Yeah. There’s a lot of restrictions on my candor in general. I realize it’s going into a public forum. While I am free to write and try to purvey myself as somebody who writes from the heart and so on, let’s be honest, I’m always circumspect about exactly what I’m going to say. That would be disingenuous to say I’m just writing everything my id suggests I write. Just like I’m not going to say anything in real life that would cause great offense or consternation to somebody.

TrunkSpace: You mentioned that the songs are representative of those periods of struggle or joy. Is songwriting almost a bit of a therapy? Is it a therapeutic practice to be able to get those emotions out?

TrunkSpace: You mentioned that the songs are representative of those periods of struggle or joy. Is songwriting almost a bit of a therapy? Is it a therapeutic practice to be able to get those emotions out?

Himmelman: Yeah, I think it is. It’s like when I’m in the kind of fecund zone of writing where things are just popping out like a hamster giving birth to a litter of 20 hamsters. They just come out. Contrasting with right now, I have zero desire to sit down on my piano, which is right in front of me.

TrunkSpace: Is the creative something that you can’t force?

Himmelman: I could force it. If somebody said to me, and this sounds crass, but anyone that writes for a living, you know how this works. If somebody said, “Look, I’m going to pay you X amount of money and I need a song by Tuesday” and that amount of money was meaningful to me, I would place myself in a position that that song would come out. In other words, I would force myself into the mood and what resulted from the mood most likely would be totally real and good. It used to be like that when I was on a label and you had to adhere to a schedule. There’s something really great about that because I need the advance check to pay the rent and then I’d be in the position to do it.

Now getting back to your premise as songs being therapeutic, yeah, once I’m in that mode, things start to emerge. I start to understand a lot about myself when some of these songs come out.

TrunkSpace: With that in mind, did you discover or learn anything about yourself in making “There Is No Calamity”?

Himmelman: Yeah. I think this is… I remember a story about Prince. He went with his wife at the time up to Northern Minnesota and looked at a lake. It’s a story I heard from a journalist who has this giant trove of unpublished Prince stuff. So they’re at the lake and it’s just so placid and cold. He was there for 10 minutes and he was like, “I got to get back to my studio. I got to write.”

Sometimes I feel that way, that the world in my head is sometimes more interesting than the world around me. That’s kind of a sad thing to say. There is something very engaging about one’s own thoughts and one’s own meanings of expression. It’s so fulfilling that sometimes it’s hard for other experiences to compete with that.

TrunkSpace: In a lot of ways, that goes back to what we talked about earlier about our parents. When you’re a kid, how you view your parents is sort of superhero-like in your head. The more you learn about them, you start to realize that they’re human. A lot of times what’s in our head is almost more interesting in a way. More fictional.

Himmelman: Yeah, and more perfect. When things come out into the open, if you want to just use songs as that metaphor, for some people, and I talk about this a lot in my book and so on… for some people, making and manifesting the fruits of their imagination is a dangerous thing. I have a friend of mine who is about as good a musician as you’d ever want to find and is really a fine songwriter/producer. I met him when he was pretty young and he, of course, wanted to make a record. That record has yet to come out and he’s no longer young. I believe that having something orbiting in your head where it is in a pristine state certainly is not subject to judgment, one’s own or other people’s judgment. It lends a very pallid sense of fulfillment. That is to say that it doesn’t lend no fulfillment. It’s like, “If I were ever to make a record, it would be amazing.” But if it comes out and it’s less than amazing and people criticize it, it could, in some people’s mind, it could kill them. Bringing things out into the world, it has its risks. It has, I guess, its dangers. I just find it’s fulfilling to not only dream up things, but to make them manifest. I suppose that’s why there’s so much material out there that I put out.

TrunkSpace: Humans are complicated beings.

Himmelman: Yeah, we’re so complicated. You’re so right, and the layers. If you keep this stuff to yourself… I have a thing where I’ll play stuff for a very select group of people. Maybe it’s one or two. I get excited about it. I’ll play and I’ll share something with somebody, get some feedback, get the fire going with some tinder or some kindling. Then, oh yeah, I’m using that to get over these hurdles of my own about my own fears. I have my own little techniques to push me, which is to say that it’s not as though I don’t have these same fears.

TrunkSpace: So often artists put all their creative eggs into one basket. They find their baby and they can’t focus on doing anything else. What’s so fascinating is that you have so many different creative outlets, even helping other creative people find their own outlets. Is it hard for you to shut down your brain and step away from that creative mindset?

Himmelman: I think so. I have had a couple of personality tests done that people have run on me. There’s certain people, I guess this is where I fit in, that thrive on a degree of adversity. Maybe that’s universal. In other words, getting something to be a simple habit or rote behavior that you just easily process over and over. It would seem like an agreeable thing. “Yeah, let’s just do that. Churn out some money.”

A lot of people would do that so that they could make money so that they could do something like touch a whale shark in the South China Sea or something. It isn’t the work that they do that they love so much, it’s the money that they earn that will allow them to do what they love. For me, the manifestation of these creative things is what I love and the challenges they present and the little hurdles.

That said, I wonder if I’d have had a huge hit, let’s say one of my albums, “Flown This Acid World”, had just been a massive hit and I had a ton of money from that, it’s possible that I wouldn’t be doing all these different things. You could say the reason I do it is just because I felt I had to. I had to keep moving and then there would definitely be truth in that, too. Then again, going back to my dad, he was the type of person who always was reinventing himself, always in an entrepreneurial sense.

Some of the stuff I’ll tell you sounds funny. We’re from Minnesota. He was the first guy to bring in Japanese motorcycles to Minnesota. Suzukis. I remember him getting a motorcycle shipping quote and thinking he was being silly but he was being deadly serious about bringing this motorcycle over. At that time, it seemed like, well, whatever. A motorcycle was a Harley Davidson or a BMW. You didn’t have a Japanese motorcycle, which was synonymous with shit made in Japan. He brought that in. He had the first 8-track tape store in Minneapolis. That sounds like a joke, but…

TrunkSpace: Not at all. It’s part of the equation. You don’t get to cassette, you don’t get to CD, you don’t get to digital without the 8-track.

Himmelman: Right. That was a huge, huge step that you could have the music of your choice in a great sounding stereo or in your car. I would watch him as a kid. He had a security camera business that got later bought out by Honeywell way too early. I mean way before we made any money on it, but all these different things. For me, that was just natural. This idea of reinvention. This idea of just taking the fruits of your imagination and making them manifest.

“There Is No Calamity” (Himmasongs/Six Degrees) is available now for digital download and will hit stores August 11.