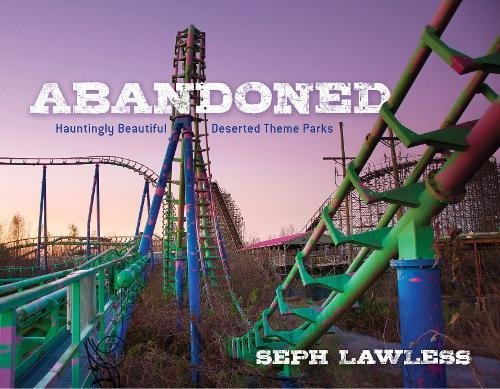

We’ve all driven by an abandoned mall, factory, or amusement park and were struck by their hauntingly silent exteriors, wondering what secrets lay inside. For photojournalist Seph Lawless (a pseudonym), the pull to peel back those layers and reveal the reality of urban decay began over a decade ago. Now, with his latest book “Abandoned: Hauntingly Beautiful Deserted Theme Parks,” the activist with an eye for finding beauty in the blight has plucked at a nostalgic chord in all of us.

We’ve all driven by an abandoned mall, factory, or amusement park and were struck by their hauntingly silent exteriors, wondering what secrets lay inside. For photojournalist Seph Lawless (a pseudonym), the pull to peel back those layers and reveal the reality of urban decay began over a decade ago. Now, with his latest book “Abandoned: Hauntingly Beautiful Deserted Theme Parks,” the activist with an eye for finding beauty in the blight has plucked at a nostalgic chord in all of us.

We recently sat down with Lawless to discuss the psychological association with being drawn to his work, the sadness he sometimes feels while on location, and why shooting amusement parks is a bit of departure from his other discarded subjects.

TrunkSpace: You started shooting in abandoned locations over a decade ago. Could you have had any idea at that time that your work in this space would have resonated with so many people and for so long?

Lawless: No. Really. When I first started doing this, I never in a million years thought that this could catapult into any kind of career whatsoever, let alone center around something that I thought was intimate and kind of small to me in my young eyes and mind. Growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, we’re part of the Rust Belt, so you would see abandoned buildings quite a bit. Now with globalization, outsourcing of those American manufacturing jobs, you suffered a lot of population loss – not just in Cleveland, but in Akron, and Youngstown, the surrounding cities, and of course where my family comes from, Detroit – of about half the population, a little bit more in Detroit since World War II.

TrunkSpace: And those people who left, their families were there for generations.

Lawless: Yes. It’s getting up and moving where the jobs are, in hopes to find other jobs. They would just leave. It would be abandoned everything – factories, schools, neighborhoods, completely abandoned ghost towns in parts, or at least seemingly to be so. Back then, it was more so, and it still is, be honest, exciting and fun to do, and I think it’s important to do.

I always wanted to show the places I was going into to a larger audience. That was the goal even early on. I didn’t know how I was going to achieve that, and then it wasn’t until popular photo sharing apps like Instagram and social media came into fruition that I said, “Hey, this is not only a viable option, but this is going to be a great, phenomenal vehicle to use to share these images with as many people as I possibly could.”

going to achieve that, and then it wasn’t until popular photo sharing apps like Instagram and social media came into fruition that I said, “Hey, this is not only a viable option, but this is going to be a great, phenomenal vehicle to use to share these images with as many people as I possibly could.”

I think from that really came other opportunities. Other journalists were writing me that the photos were striking and stunning and that they were telling an untold chapter of American history. Journalists were latching on left and right, from CNN to NBC News, ABC, global entities – and they were expanding the narrative. They were taking my images, and then expanding the narrative into social issues or economic issues, or consumer changing habits if it was like an abandoned mall.

No, I never thought it would go as far as I did to where my images are on the cover of a Shirley Jackson book and album covers. I would have in a million years never thought that. And by the way, I never tried to achieve that, either. Those things just came.

TrunkSpace: Do you think it says anything psychologically about people having a fascination with your work and seeing this almost post apocalyptic side of society?

Lawless: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. It’s not one that’s posed to me a lot, but it’s one I do think about a lot. I think there is something deeper in the psychology of people – why they’re resonating with it. I think there’s an element of fear. They don’t want to be afraid, and they don’t want these horrible things to necessarily happen to them, or their country, or their environment, but they’re comfortable watching it from a distance, like a scary movie. No one wants to be chased around with an axe and a knife, but yet, you’re honing in on that fear. You almost are controlling it. It almost becomes empowering.

I think there’s a little bit of that in a sense to whereas, “If the world ended, this is what it would look like!” We could safely look, and I think you have that with this zombie apocalypse or “Stranger Things” kind of addiction where we’re asked, “The world is ending, oh hell, what are we going to do?” What would it be like? What would those final moments be? It’s almost become sort of a fixation amongst society today, I think. Not just in my work, but I think in movies and genres and television shows and comic books – all of those things. I think now more than ever, there seems to be that element of wanting to dip their toes into fear a little bit, but not get too close.

TrunkSpace: In a way, we the viewer end up being more of a problem than the solution. There could be a mall in our hometown that we don’t want to see close, and yet, we don’t shop there. We’re sad when it’s gone, but we did very little to stop it.

Lawless: Yeah. I think so, but it’s also what we care about, right? I’m older too, I grew up with malls, I get sad too, and I get upset, like you said, about the mall closing, but you don’t go there. The thing is, we’re moved and we miss the mall – the things that were attached to the mall – but we don’t miss going to the mall, because listen, growing up, it was a communal space. We met our friends there, even when we couldn’t afford things. We played at the arcade, might have kissed your first girlfriend there. You shared emotional, joyous occasions, or sad ones, whatever the case may be. People share a very personal testimony with malls, and abandoned amusement parks. Amusement parks over the years, people would go multiple times. When you’re dealing with large spaces that deal with hundreds of thousands of people – millions that attended these places over the years – they’re going to share memories. I think that’s what people miss most with malls.

By the way, I think they miss the way we used to communicate. Malls were the chat room before there was a chat room. Before there was social media, before there were phones, before there were pagers even, you said, “Hey buddy… Billy, meet me after school at the mall,” or we got dropped off at the mall. That’s how we communicated. It was face to face. It was eye contact. Most of the time it was a physical response, and I think lacking that, I think people long for a time more than the entity itself, the structure itself.

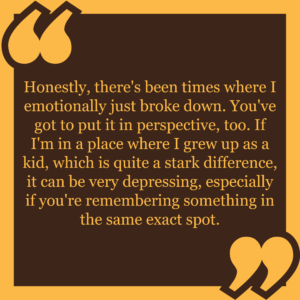

TrunkSpace: Your work can jump start a bunch of different emotional responses, but the one we always end up at is sadness because here are these places that were once filled with laughter and joy and such life, and now all of that is gone. Do you experience that while on location? Does the sadness of being in those spaces in their current form hit you?

Lawless: Oh yeah, quite a bit. Honestly, there’s been times where I emotionally just broke down. You’ve got to put it in perspective, too. If I’m in a place where I grew up as a kid, which is quite a stark difference, it can be very depressing, especially if you’re remembering something in the same exact spot. You just get inundated with these memories that you had there. That can be very sad.

The most toxic place in America? That’s troubling on so many deep, different levels. That makes you sad and angry and upset, and livid at times. Emotions will change based on where I’m at, but yeah, of course, emotionally it can be draining.

TrunkSpace: Can it be dangerous work? After all, you’re entering these abandoned places that probably aren’t always abandoned. People must be staying in some of the places you shoot at, right?

Lawless: Yeah, there is, and it’s technically their home. There can also be cases of trespassing involved with these things, too. Over the years, I’m very careful – usually I can tell before I go into an abandoned building. There are little tells you look for, if it’s going to be occupied or if there’s someone in it. I do my best to not violate their personal space. I treat it like that’s their home. It’s just as awkward a feeling as if you were to walk into someone’s home unannounced and try to rob it or something. You get that same uneasy feeling, or I would imagine so. You don’t necessarily belong there.

Beyond that, I’ve fallen through floors up to my waist and caught myself. I’ve had parts of ceilings fall on me. I was in a mansion, a beautiful, hauntingly beautiful mansion that I shot in Pennsylvania. I loved it. As I walked in, I went all the way upstairs and my feet were sinking. It was almost like I was walking on water. It was horrible. Then I get home, and a couple of weeks later the local newspaper said half of the mansion crumbled onto the sidewalk. They used that as a pretext to tear down the whole thing, but it very well could have come down. That was a stupid thing for me to do. After that, and that happened about a year ago, I don’t nearly take as many risks. If I was in that same situation again, I wouldn’t walk up all the way. I might not even go inside anymore. There’s some that have gotten so bad that I won’t go back in.

TrunkSpace: Your new book focuses on amusement parks. Visually, what do they offer your eye that other locations don’t?

Lawless: A lot of the projects that I’ve done have dealt with various issues, from neglect or environmental issues or a horrible changing landscape of consumer habits. With this, it was more of a fun thing to do. I always thought abandoned amusement parks were interesting visually. They’re always fun to shoot.

A lot of people don’t know this, but I try to shoot them in bad weather, believe it or not, to get those dramatic effects. There was one in particular where a tornado came through and I sped away. It was horrible weather, out in Kansas during tornado season. I would go back multiple times to get it exactly how I wanted, for most of them. There’s a few that were the exception. There was a lot of thought behind the images, how I was going to portray them, how I was going to shoot them.

To me, I always thought they were fun to shoot, mainly because they were outside. You have great a backdrop, you have clouds, you have sky, you have sun. It’s a little bit different. It’s more so landscape photography, in a sense.

“Abandoned: Hauntingly Beautiful Deserted Theme Parks” is available now.